Nature | Letter

Quantum teleportation of multiple degrees of freedom of a single photon

- Journal name:

- Nature

- Volume:

- 518,

- Pages:

- 516–519

- Date published:

- DOI:

- doi:10.1038/nature14246

- Received

- Accepted

- Published online

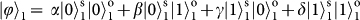

Quantum teleportation1 provides a ‘disembodied’ way to transfer quantum states from one object to another at a distant location, assisted by previously shared entangled states and a classical communication channel. As well as being of fundamental interest, teleportation has been recognized as an important element in long-distance quantum communication2, distributed quantum networks3 and measurement-based quantum computation4, 5. There have been numerous demonstrations of teleportation in different physical systems such as photons6, 7, 8, atoms9, ions10, 11, electrons12 and superconducting circuits13. All the previous experiments were limited to the teleportation of one degree of freedom only. However, a single quantum particle can naturally possess various degrees of freedom—internal and external—and with coherent coupling among them. A fundamental open challenge is to teleport multiple degrees of freedom simultaneously, which is necessary to describe a quantum particle fully and, therefore, to teleport it intact. Here we demonstrate quantum teleportation of the composite quantum states of a single photon encoded in both spin and orbital angular momentum. We use photon pairs entangled in both degrees of freedom (that is, hyper-entangled) as the quantum channel for teleportation, and develop a method to project and discriminate hyper-entangled Bell states by exploiting probabilistic quantum non-demolition measurement, which can be extended to more degrees of freedom. We verify the teleportation for both spin–orbit product states and hybrid entangled states, and achieve a teleportation fidelity ranging from 0.57 to 0.68, above the classical limit. Our work is a step towards the teleportation of more complex quantum systems, and demonstrates an increase in our technical control of scalable quantum technologies.

Subject terms:

At a glance

Figures

-

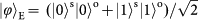

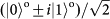

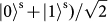

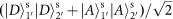

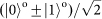

Figure 1: Scheme for quantum teleportation of the spin–orbit composite states of a single photon. a, Alice wishes to teleport to Bob the quantum state of a single photon 1 encoded in both its SAM and OAM. To do so, Alice and Bob need to share a hyper-entangled photon pair 2–3. Alice then carries out an h-BSM assisted by a QND measurement (see main text for details) and sends the results as four-bit classical information to Bob. On receiving Alice’s h-BSM result, Bob can apply appropriate Pauli operations (denoted Uo and Us for the OAM and SAM DoFs, respectively) on photon 3 to convert it into the original state of photon 1. The active feed-forward is essential for a full, deterministic teleportation. In our present proof-of-principle experiment, we did not apply feed-forward but used post-selection to verify the success of teleportation. BS, beam splitter. b, Teleportation-based probabilistic QND measurement with an ancillary entangled photon pair. An incoming photon can cause a coincidence detection after the beam splitter, which heralds its presence and meanwhile fully teleports its arbitrary unknown quantum state (|Φ

) to a free-flying photon. In the case of no incoming photon, the coincidence event after the beam splitter cannot happen, thus indicating the photon’s absence.

) to a free-flying photon. In the case of no incoming photon, the coincidence event after the beam splitter cannot happen, thus indicating the photon’s absence. -

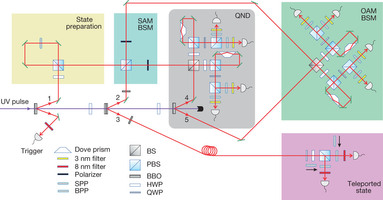

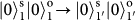

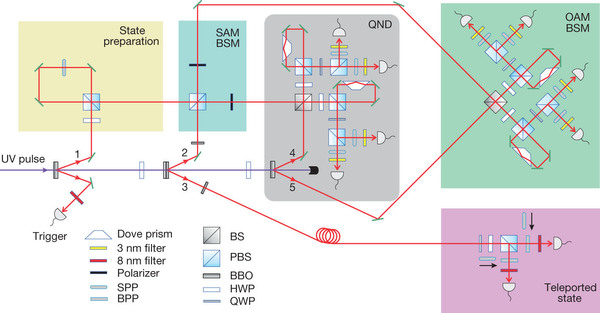

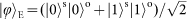

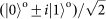

Figure 2: Experimental set-up for teleporting multiple properties of a single photon. A pulsed ultraviolet (UV) laser is focused on three β-barium borate (BBO) crystals and produces three photon pairs in spatial modes 1–t, 2–3 and 4–5. Triggered by its sister photon, t, photon 1 is initialised in various spin-orbit composite states (

) to be teleported. The second pair, 2–3, is hyper-entangled in both SAM and OAM. The third pair, 4–5, is OAM-entangled. The h-BSMs for photons 1 and 2 are performed in three steps: (1) SAM BSM; (2) QND measurement; (3) OAM BSM. The teleported state is measured separately in SAM and OAM: a PBS, a half-wave plate (HWP) and a quarter-wave plate (QWP) are combined for SAM qubit analysis, and an SPP or a BPP together with a single-mode fibre are used for OAM qubit analysis.

) to be teleported. The second pair, 2–3, is hyper-entangled in both SAM and OAM. The third pair, 4–5, is OAM-entangled. The h-BSMs for photons 1 and 2 are performed in three steps: (1) SAM BSM; (2) QND measurement; (3) OAM BSM. The teleported state is measured separately in SAM and OAM: a PBS, a half-wave plate (HWP) and a quarter-wave plate (QWP) are combined for SAM qubit analysis, and an SPP or a BPP together with a single-mode fibre are used for OAM qubit analysis. -

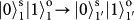

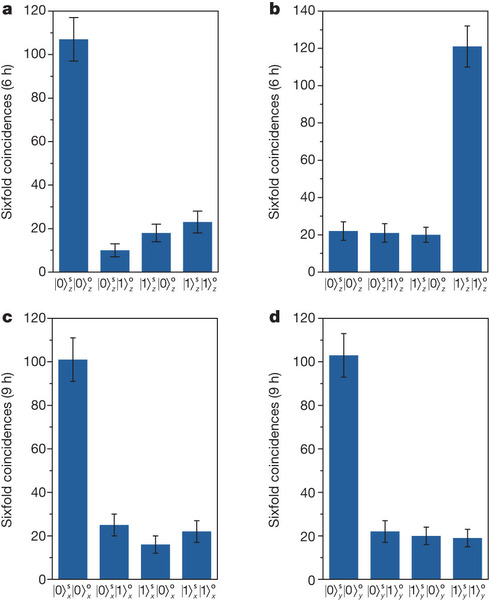

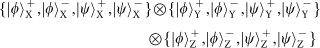

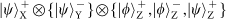

Figure 3: Experimental results for quantum teleportation of spin–orbit product states  ,

,

,

,

and

and

of a single photon.

of a single photon.

a, b, Measurement results of the final state of the teleported photon 3 in the

and

and

bases for the

bases for the

(a) and

(a) and

(b) teleportation experiment. c, The results for the

(b) teleportation experiment. c, The results for the

teleportation, measured in the

teleportation, measured in the

and

and

bases. d, The results for the

bases. d, The results for the

teleportation, measured in the

teleportation, measured in the

and

and

bases. The x axis uses Pauli notation for both DoFs:

bases. The x axis uses Pauli notation for both DoFs:

,

,

and

and

. The y axis is six-photon coincidence counts. Error bars, 1 s.d., calculated from Poissonian counting statistics of the raw detection events.

. The y axis is six-photon coincidence counts. Error bars, 1 s.d., calculated from Poissonian counting statistics of the raw detection events. -

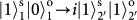

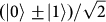

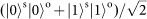

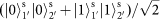

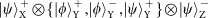

Figure 4: Experimental results for quantum teleportation of spin–orbit entanglement of a single photon. a–c, To determine the state fidelity of the teleported entangled state,

, three measurement bases are required:

, three measurement bases are required:

and

and

(a),

(a),

and

and

(b), and

(b), and

and

and

(c). These are used to extract the expectation values of the joint Pauli observables

(c). These are used to extract the expectation values of the joint Pauli observables

,

,

and

and

, respectively. Each measurement takes 12 h. The data set in a determines the population of the two desired terms:

, respectively. Each measurement takes 12 h. The data set in a determines the population of the two desired terms:

and

and

in the entangled state,

in the entangled state,

. The data set in b and c measured in the superposition basis determines the coherence of the entangled state. We use the same Pauli notation as in Fig. 3. d, A summary of the teleportation fidelities for the states

. The data set in b and c measured in the superposition basis determines the coherence of the entangled state. We use the same Pauli notation as in Fig. 3. d, A summary of the teleportation fidelities for the states

. Error bars, 1 s.d., deduced from propagated Poissonian counting statistics of the raw detection events.

. Error bars, 1 s.d., deduced from propagated Poissonian counting statistics of the raw detection events. -

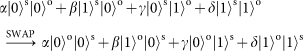

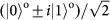

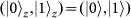

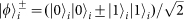

Extended Data Fig. 1: Hong–Ou–Mandel interference of multiple independent photons encoded with SAM or OAM. a, Interference at the PBS where input photons 1 and 2 are intentionally prepared in the states

(orthogonal SAMs; open squares) and

(orthogonal SAMs; open squares) and

(parallel SAMs; solid circles). The y axis shows the raw fourfold (the trigger photon t and photons 1, 2 and 3) coincidence counts. The extracted visibility is 0.75 ± 0.03, calculated from V(0) = (C+ − C//)/(C+ + C//), where C// and C+ are the coincidence counts without any background subtraction at zero delay for parallel and, respectively, orthogonal SAMs. The red and blue lines are Gaussian fits to the raw data. b, Two-photon interference on beam splitter 1, where photons 1 and 4 are prepared in orthogonal OAM states. The black line is a Gaussian fit to the raw data of fourfold (the trigger photon and photons 1, 4 and 5) coincidence counts. The visibility is 0.73 ± 0.03, calculated from V(0) = 1 – C0/C∞, where C0 and C∞ is the fitted counts at zero and, respectively, infinite delays. c, Two-photon interference at beam splitter 2, where input photons 1 and 5 are prepared in the orthogonal OAM states. The black line is a Gaussian fit to the data points. The interference visibility is 0.69 ± 0.03 calculated in the same way as in b. Error bars, 1 s.d., calculated from Poissonian counting statistics of the raw detection events.

(parallel SAMs; solid circles). The y axis shows the raw fourfold (the trigger photon t and photons 1, 2 and 3) coincidence counts. The extracted visibility is 0.75 ± 0.03, calculated from V(0) = (C+ − C//)/(C+ + C//), where C// and C+ are the coincidence counts without any background subtraction at zero delay for parallel and, respectively, orthogonal SAMs. The red and blue lines are Gaussian fits to the raw data. b, Two-photon interference on beam splitter 1, where photons 1 and 4 are prepared in orthogonal OAM states. The black line is a Gaussian fit to the raw data of fourfold (the trigger photon and photons 1, 4 and 5) coincidence counts. The visibility is 0.73 ± 0.03, calculated from V(0) = 1 – C0/C∞, where C0 and C∞ is the fitted counts at zero and, respectively, infinite delays. c, Two-photon interference at beam splitter 2, where input photons 1 and 5 are prepared in the orthogonal OAM states. The black line is a Gaussian fit to the data points. The interference visibility is 0.69 ± 0.03 calculated in the same way as in b. Error bars, 1 s.d., calculated from Poissonian counting statistics of the raw detection events. -

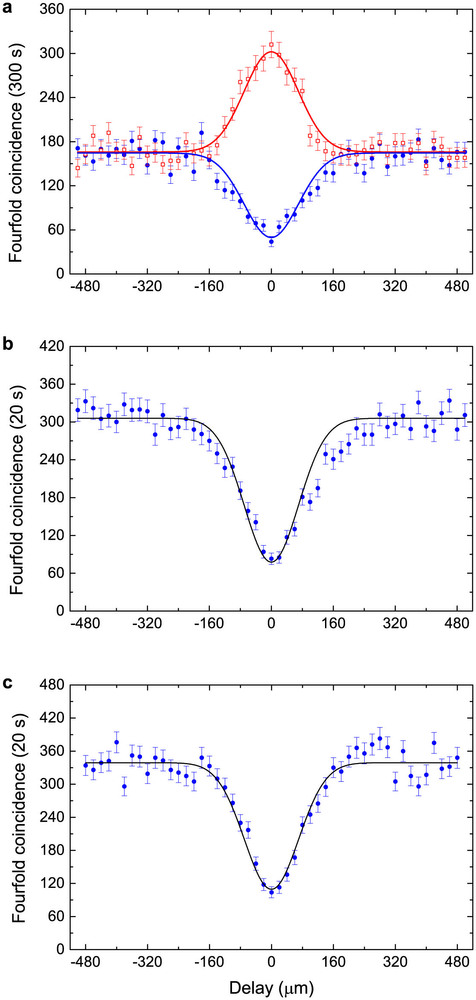

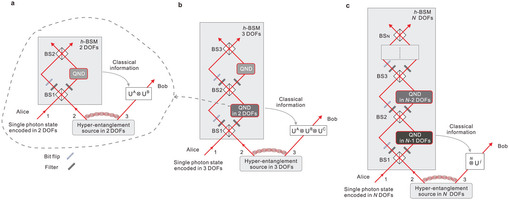

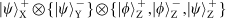

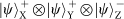

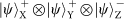

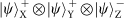

Extended Data Fig. 2: A universal scheme for teleporting N DoFs of a single photons. a, A scheme for teleporting two DoFs of a single photon using three beam splitters, which is slightly different from the one presented in the main text using a PBS and two beam splitters. Through the first beam splitter, six asymmetric states,

and

and

, can result in one photon in each output, which is ensured by teleportation-based QND on the Y DoF. After passing the two photons through the two filters that project them into the

, can result in one photon in each output, which is ensured by teleportation-based QND on the Y DoF. After passing the two photons through the two filters that project them into the

and

and

states for the X DoF, four states,

states for the X DoF, four states,

and

and

, survive. Through the second beam splitter, only the asymmetric state

, survive. Through the second beam splitter, only the asymmetric state

of the Y DoF can result in one photon in each output. Finally we can discriminate the state

of the Y DoF can result in one photon in each output. Finally we can discriminate the state

from the 16 hyper-entangled Bell states. b, Teleportation of three DoFs of a single photons (Methods). Note that to ensure that there is one and only one photon in the output of the first beam splitter, we can use the teleportation-based QND on two DoFs in a (dashed circle). c, Generalized teleportation of N DoFs of a single photons. The h-BSM on N DoFs can be implemented as follows: (1) the beam splitter post-selects the asymmetric hyper-entangled Bell states in N DoFs which contain an odd number of asymmetric Bell states in one DoF, (2) two filters and one bit-flip operation erase the information on the measured DoF and further post-select asymmetric states, and (3) teleportation-based QND.

from the 16 hyper-entangled Bell states. b, Teleportation of three DoFs of a single photons (Methods). Note that to ensure that there is one and only one photon in the output of the first beam splitter, we can use the teleportation-based QND on two DoFs in a (dashed circle). c, Generalized teleportation of N DoFs of a single photons. The h-BSM on N DoFs can be implemented as follows: (1) the beam splitter post-selects the asymmetric hyper-entangled Bell states in N DoFs which contain an odd number of asymmetric Bell states in one DoF, (2) two filters and one bit-flip operation erase the information on the measured DoF and further post-select asymmetric states, and (3) teleportation-based QND. -

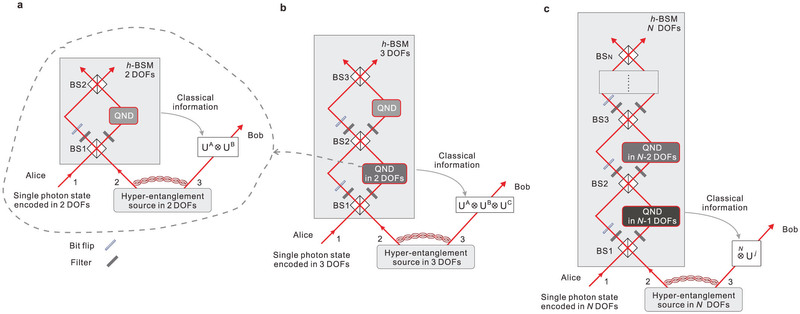

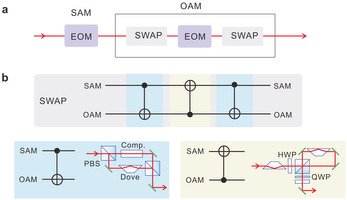

Extended Data Fig. 3: Active feed-forward for spin–orbit composite states. a, The active feed-forward scheme. This composite active feed-forward could be completed in a step-by-step manner. First, we use an EOM to implement the active feed-forward for SAM qubits. It is important to note that EOM does not affect OAM. Second, we use a coherent quantum SWAP gate between the OAM and SAM qubits. The original OAM is converted into a ‘new’ SAM, whose active feed-forward operation is done by a second EOM. Then the OAM and SAM qubits undergo a second SWAP operation and are converted to the original DoFs. b, The quantum circuit for a SWAP gate between the OAM and SAM qubits. The SWAP gate is composed of three CNOT gates: in the first and third CNOT gates, the SAM and OAM qubits act as the control and target qubits, respectively, whereas in the second CNOT gate this is reversed.

and

and

denote horizontal and vertical polarizations of the SAM;

denote horizontal and vertical polarizations of the SAM;

and

and

refer to right-handed and left-handed OAMs of

refer to right-handed and left-handed OAMs of

and

and

, respectively; and

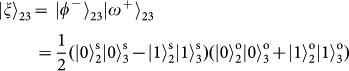

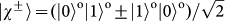

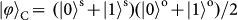

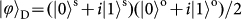

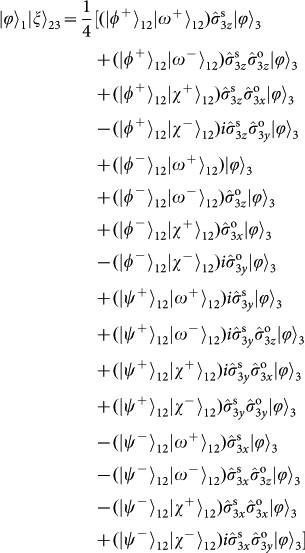

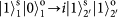

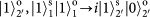

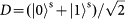

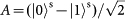

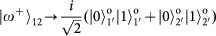

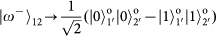

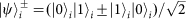

, respectively; and  . For Alice to do so, she and Bob first need to share a hyper-entangled photon pair (photons 2 and 3), which is simultaneously entangled in both SAM and OAM:

. For Alice to do so, she and Bob first need to share a hyper-entangled photon pair (photons 2 and 3), which is simultaneously entangled in both SAM and OAM:

and

and

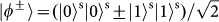

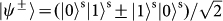

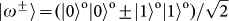

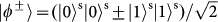

to denote the four Bell states encoded in SAM, and

to denote the four Bell states encoded in SAM, and

and

and

to denote the four Bell states in OAM. Their tensor products result in a group of 16 hyper-entangled Bell states.

to denote the four Bell states in OAM. Their tensor products result in a group of 16 hyper-entangled Bell states.

, photon 3 will be projected onto the initial state of photon 1:

, photon 3 will be projected onto the initial state of photon 1:

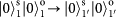

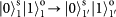

) and reflects vertical polarization (

) and reflects vertical polarization (

). After the PBS, we post-select the event that there is one and only one photon in each output. Such an event can occur only if the two input photons have the same SAM (both are transmitted (

). After the PBS, we post-select the event that there is one and only one photon in each output. Such an event can occur only if the two input photons have the same SAM (both are transmitted (

) or reflected (

) or reflected (

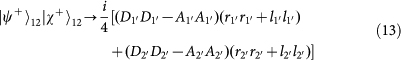

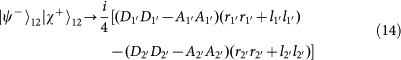

)), which projects the SAM part of the wavefunction into the two-dimensional subspace spanned by

)), which projects the SAM part of the wavefunction into the two-dimensional subspace spanned by

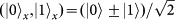

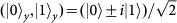

. At both outputs of the PBS, we add two polarizers, projecting the two photons into the diagonal basis

. At both outputs of the PBS, we add two polarizers, projecting the two photons into the diagonal basis

. It should be noted that the PBS is not OAM-preserving

. It should be noted that the PBS is not OAM-preserving ,

,

,

,

and

and

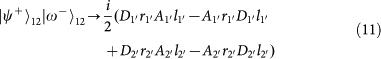

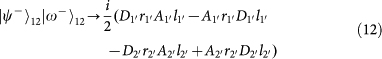

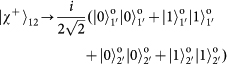

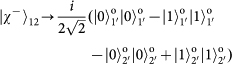

. Thus, both the SAM and the OAM must be taken into account as in a molecular-like coupled state. A detailed mathematical treatment is presented in Methods, showing that the PBS and two polarizers select the four following states out of the total 16 hyper-entangled Bell states:

. Thus, both the SAM and the OAM must be taken into account as in a molecular-like coupled state. A detailed mathematical treatment is presented in Methods, showing that the PBS and two polarizers select the four following states out of the total 16 hyper-entangled Bell states:

,

,

,

,

and

and

.

. can be distinguished by a coincidence detection in separate outputs, and

can be distinguished by a coincidence detection in separate outputs, and

can be discriminated by measuring two orthogonal OAMs in either output. In total, these two steps would allow an unambiguous discrimination of the two hyper-entangled Bell states

can be discriminated by measuring two orthogonal OAMs in either output. In total, these two steps would allow an unambiguous discrimination of the two hyper-entangled Bell states

and

and

.

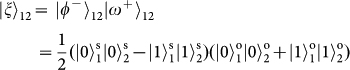

. . The third pair (4–5) is prepared in the ancillary OAM-entangled state

. The third pair (4–5) is prepared in the ancillary OAM-entangled state

for the teleportation-based QND measurement.

for the teleportation-based QND measurement.

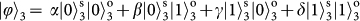

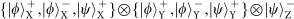

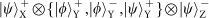

,

,

,

,

,

,

and

and

. These states can be grouped into three categories:

. These states can be grouped into three categories:

and

and

are product states of the two DoFs in the computational basis;

are product states of the two DoFs in the computational basis;

and

and

are products states of the two DoFs in the superposition basis; and

are products states of the two DoFs in the superposition basis; and

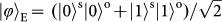

is a spin–orbit hybrid entangled state. The four product states are prepared by independent single-qubit rotations, using wave plates for SAM and spiral phase plates (SPPs) or binary phase plates (BPPs) for OAM. The entangled state is generated by counter-propagating a SPP inside a Sagnac interferometer (Methods).

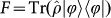

is a spin–orbit hybrid entangled state. The four product states are prepared by independent single-qubit rotations, using wave plates for SAM and spiral phase plates (SPPs) or binary phase plates (BPPs) for OAM. The entangled state is generated by counter-propagating a SPP inside a Sagnac interferometer (Methods). , which is defined as the overlap of the ideal teleported state (

, which is defined as the overlap of the ideal teleported state (

) and the measured density matrix (

) and the measured density matrix (

). Conditioned on the detection of the trigger photon t and the four-photon coincidence after the h-BSM, we register the photon counts of teleported photon 3 and analyse its composite state. The fidelity measurements for the product states are straightforward because we can measure the SAM and OAM qubits separately. We measure the final state in the

). Conditioned on the detection of the trigger photon t and the four-photon coincidence after the h-BSM, we register the photon counts of teleported photon 3 and analyse its composite state. The fidelity measurements for the product states are straightforward because we can measure the SAM and OAM qubits separately. We measure the final state in the

and

and

bases for the teleportation of

bases for the teleportation of

and

and

, in the

, in the

and

and

bases for the teleportation of

bases for the teleportation of

, and in the

, and in the

and

and

bases for the teleportation of

bases for the teleportation of

. The data in

. The data in  ,

,

,

,

and, respectively,

and, respectively,

.

.

, where the SAM and OAM qubits are not separable, can be decomposed as

, where the SAM and OAM qubits are not separable, can be decomposed as

, where

, where  ,

,

and

and

can be obtained by local measurements in the corresponding basis for the two DoFs,

can be obtained by local measurements in the corresponding basis for the two DoFs,

,

,

and

and

, respectively. Our experimental results on the three different bases are presented in

, respectively. Our experimental results on the three different bases are presented in

, we emphasize that the teleportation fidelity exceeds the threshold of 0.5 required to prove the presence of entanglement

, we emphasize that the teleportation fidelity exceeds the threshold of 0.5 required to prove the presence of entanglement

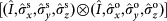

,

,

,

,

) and (

) and (

,

,

,

,

) are the Pauli operators for the SAM and, respectively, the OAM qubits. It indicates that, regardless of the unknown state

) are the Pauli operators for the SAM and, respectively, the OAM qubits. It indicates that, regardless of the unknown state

, the 16 measurement outcomes are equally likely, each with a probability of 1/16. By carrying out the hyper-entangled Bell state measurement (h-BSM) on photons 1 and 2 to unambiguously distinguish one from the group of 16 hyper-entangled Bell states, Alice can project photon 3 onto one of the 16 corresponding states. After Alice tells Bob her h-BSM result as four-bit classical information via a classical communication channel, Bob can convert the state of his photon 3 into the original state by applying appropriate two-qubit local unitary transformations

, the 16 measurement outcomes are equally likely, each with a probability of 1/16. By carrying out the hyper-entangled Bell state measurement (h-BSM) on photons 1 and 2 to unambiguously distinguish one from the group of 16 hyper-entangled Bell states, Alice can project photon 3 onto one of the 16 corresponding states. After Alice tells Bob her h-BSM result as four-bit classical information via a classical communication channel, Bob can convert the state of his photon 3 into the original state by applying appropriate two-qubit local unitary transformations

.

. ,

,

,

,

,

,

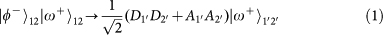

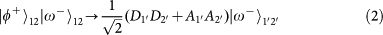

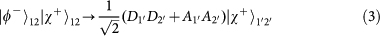

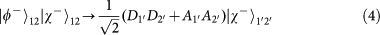

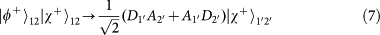

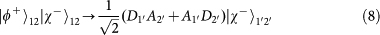

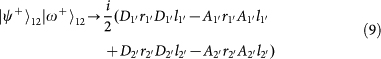

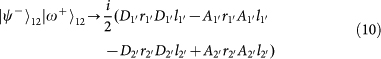

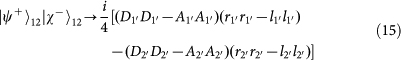

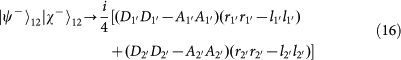

. Note that the PBS is not OAM-preserving, because the reflection flips the sign of OAM. Therefore, the output state for each of the input 16 hyper-entangled Bell states can be listed below:

. Note that the PBS is not OAM-preserving, because the reflection flips the sign of OAM. Therefore, the output state for each of the input 16 hyper-entangled Bell states can be listed below:

,

,

,

,

and

and

. Then both of the output modes are passing through two polarizers at

. Then both of the output modes are passing through two polarizers at

. Only the output with the term

. Only the output with the term

will result in there being one photon in each output mode with an efficiency of 1/8. The other terms will be rejected by the conditional detection. According to equations (1)–(16), 4 of the 16 output modes have the term

will result in there being one photon in each output mode with an efficiency of 1/8. The other terms will be rejected by the conditional detection. According to equations (1)–(16), 4 of the 16 output modes have the term

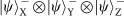

and the 4 corresponding input hyper-entangled Bell states are

and the 4 corresponding input hyper-entangled Bell states are

,

,

,

,

and

and

, which will be sent to the next stage of BSM on the OAM qubits.

, which will be sent to the next stage of BSM on the OAM qubits.

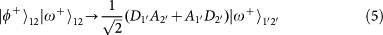

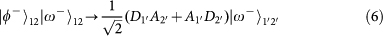

will result in there being one and only one photon in each output, whereas for the three other Bell states the two input photons will coalesce into a single output mode. Among these three Bell states, the state

will result in there being one and only one photon in each output, whereas for the three other Bell states the two input photons will coalesce into a single output mode. Among these three Bell states, the state

can be further distinguished by measuring two single photons in either output with the OAM orthogonal basis

can be further distinguished by measuring two single photons in either output with the OAM orthogonal basis

. Thus, this would allow us to unambiguously discriminate two from the four Bell states. Experimentally, we design dual-channel OAM readout devices to measure

. Thus, this would allow us to unambiguously discriminate two from the four Bell states. Experimentally, we design dual-channel OAM readout devices to measure

and

and

simultaneously. Therefore, the efficiency of both QND and BSM on OAM is 1/2. The overall efficiency of h-BSM combining all three steps is

simultaneously. Therefore, the efficiency of both QND and BSM on OAM is 1/2. The overall efficiency of h-BSM combining all three steps is

.

. In SPDC, the zero-order OAM mode has the highest weight among all OAM modes and thus has the highest brightness. The second photon pair (2–3) is simultaneously entangled in both the SAM and the OAM (in the first-order mode), owing to OAM conservation in the type-I SPDC. It has a count rate of

In SPDC, the zero-order OAM mode has the highest weight among all OAM modes and thus has the highest brightness. The second photon pair (2–3) is simultaneously entangled in both the SAM and the OAM (in the first-order mode), owing to OAM conservation in the type-I SPDC. It has a count rate of

and a state fidelity of 0.95. The third photon pair (4–5) is created in the first-order OAM entangled state with a two-photon count rate of

and a state fidelity of 0.95. The third photon pair (4–5) is created in the first-order OAM entangled state with a two-photon count rate of

and a fidelity of 0.91. We estimate the mean numbers of photon pairs generated per pulse as ~0.1, ~0.01 and ~0.05 for the first, second and third pairs, respectively.

and a fidelity of 0.91. We estimate the mean numbers of photon pairs generated per pulse as ~0.1, ~0.01 and ~0.05 for the first, second and third pairs, respectively. . Photon 1 is initially prepared in the

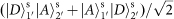

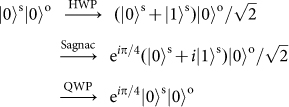

. Photon 1 is initially prepared in the

SAM state with zero-order OAM. It is then sent into a Sagnac interferometer that consists of a PBS and an SPP, where the counter-propagating

SAM state with zero-order OAM. It is then sent into a Sagnac interferometer that consists of a PBS and an SPP, where the counter-propagating

and

and

SAMs with zero-order OAM pass through the SPP in opposite directions and are converted into

SAMs with zero-order OAM pass through the SPP in opposite directions and are converted into

and

and

, respectively. Considering an extra

, respectively. Considering an extra  . We note that the whole conversion process is deterministic.

. We note that the whole conversion process is deterministic. (orthogonal SAMs; see open squares in

(orthogonal SAMs; see open squares in  (parallel SAMs; see solid circles in

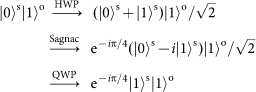

(parallel SAMs; see solid circles in  basis (1′ and 2′ denote the output spatial modes). At zero delay, where the photons are optimally overlapped in time, the orthogonal SAM input yields an output state of

basis (1′ and 2′ denote the output spatial modes). At zero delay, where the photons are optimally overlapped in time, the orthogonal SAM input yields an output state of

conditioned on a coincidence detection, which can be decomposed in the diagonal basis as

conditioned on a coincidence detection, which can be decomposed in the diagonal basis as

, thus showing an enhancement. For the parallel SAM input, the output state is

, thus showing an enhancement. For the parallel SAM input, the output state is

, which shows a reduction. The increase in the delay gradually destroys the indistinguishability of the two photons, such that their quantum state becomes a classical mixture. Thus, at large delays the counts appear flat. Interferometers of this type are sensitive only to length changes of the order of the coherence length of the detected photons and stay stable for weeks.

, which shows a reduction. The increase in the delay gradually destroys the indistinguishability of the two photons, such that their quantum state becomes a classical mixture. Thus, at large delays the counts appear flat. Interferometers of this type are sensitive only to length changes of the order of the coherence length of the detected photons and stay stable for weeks. . They are then sent into Sagnac interferometers with a Dove prism inside

. They are then sent into Sagnac interferometers with a Dove prism inside SAM component when passing through the Dove prism forwards and by an angle of –

SAM component when passing through the Dove prism forwards and by an angle of – SAM component when passing through the Dove prism backwards. OAM states

SAM component when passing through the Dove prism backwards. OAM states

and

and

with respective phases

with respective phases

and

and

, where

, where

is the azimuthal angle in the polar coordinate system, which pass through a Dove prism rotated by

is the azimuthal angle in the polar coordinate system, which pass through a Dove prism rotated by  and

and

, respectively. Therefore, two opposite phases,

, respectively. Therefore, two opposite phases,

and

and

, will be added to the two orthogonal OAM modes. Finally, the output photons are transformed into the

, will be added to the two orthogonal OAM modes. Finally, the output photons are transformed into the

and

and

polarizations using a QWP. The overall transformations can be summarized as a CNOT gate between the OAM and SAM:

polarizations using a QWP. The overall transformations can be summarized as a CNOT gate between the OAM and SAM:

, where l is an integer and is referred to as topological charge. The SPP can attach vortex phases of

, where l is an integer and is referred to as topological charge. The SPP can attach vortex phases of

and

and

to a photon when it passes through the SPP forwards and, respectively, backwards. When vortex phases of

to a photon when it passes through the SPP forwards and, respectively, backwards. When vortex phases of

and

and

are attached, the corresponding OAM values will increase by and, respectively, decrease by

are attached, the corresponding OAM values will increase by and, respectively, decrease by

. Therefore, a SPP can be used as an OAM mode converter. In our experiment, the OAM qubits are encoded in the OAM first-order subspace with the topological charge l being 1. The conversion between the OAM zero mode and the first-order modes (

. Therefore, a SPP can be used as an OAM mode converter. In our experiment, the OAM qubits are encoded in the OAM first-order subspace with the topological charge l being 1. The conversion between the OAM zero mode and the first-order modes (

and

and

) is realized using a 16-phase-level SPP with an efficiency of ~97%.

) is realized using a 16-phase-level SPP with an efficiency of ~97%. and

and

, a 2-phase-level BPP

, a 2-phase-level BPP ,

,

and

and

by ~5%. However, for the states

by ~5%. However, for the states

and

and

where the photon is horizontally or vertically polarized, the actual teleportation does not require two-photon interference at the PBS, and is therefore immune to the imperfection of the interference. This explains why the teleportation fidelities for the states

where the photon is horizontally or vertically polarized, the actual teleportation does not require two-photon interference at the PBS, and is therefore immune to the imperfection of the interference. This explains why the teleportation fidelities for the states

and

and

are the highest. This is inconsistent with the previous results: for the experiments using a PBS

are the highest. This is inconsistent with the previous results: for the experiments using a PBS , is the lowest, which is affected by the imperfection (~8%) in the state preparation of the initial state

, is the lowest, which is affected by the imperfection (~8%) in the state preparation of the initial state

as well as by imperfections in

as well as by imperfections in

and

and

, that is, essentially all error and noise present in the experiment. It can be expected that all entangled states are subject to the same decoherence mechanism as the state

, that is, essentially all error and noise present in the experiment. It can be expected that all entangled states are subject to the same decoherence mechanism as the state

as demonstrated, and should undergo similar reductions in fidelity.

as demonstrated, and should undergo similar reductions in fidelity.

or

or

(with a functionality similar to the polarizers for SAM), qubit flip (

(with a functionality similar to the polarizers for SAM), qubit flip (

) operations for the DoFs, a 50:50 non-polarizing beam splitter and single-photon detectors, all of which are commercially available or have been experimentally demonstrated previously.

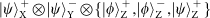

) operations for the DoFs, a 50:50 non-polarizing beam splitter and single-photon detectors, all of which are commercially available or have been experimentally demonstrated previously. state. As now we have three DoFs, we have to consider the combined, molecular-like quantum states. There are in total 28 possible combinations that are asymmetric states, as follows:

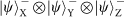

state. As now we have three DoFs, we have to consider the combined, molecular-like quantum states. There are in total 28 possible combinations that are asymmetric states, as follows:

. One filter is set to pass the

. One filter is set to pass the

state and the other is set to pass the

state and the other is set to pass the

state. This results in the following 16 states being filtered from the 28:

state. This results in the following 16 states being filtered from the 28:

state and the other set in the

state and the other set in the

state, which leaves four asymmetric combinations:

state, which leaves four asymmetric combinations:

, from the 64 hyper-entangled Bell states on three DoFs.

, from the 64 hyper-entangled Bell states on three DoFs.