Leonardo da Vinci's studies of friction

Highlights

- •

This is the first detailed chronological study of Leonardo's work on friction.

- •

Leonardo first stated the ‘laws’ of sliding friction in 1493.

- •

The widely-reproduced drawings from his notebooks date from 7-12 years later.

- •

His research was motivated by numerous practical mechanical problems.

- •

Leonardo holds a unique position as a pioneer in tribology.

Abstract

Based on a detailed study of Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks, this review examines the development of his understanding of the laws of friction and their application. His work on friction originated in studies of the rotational resistance of axles and the mechanics of screw threads. He pursued the topic for more than 20 years, incorporating his empirical knowledge of friction into models for several mechanical systems. Diagrams which have been assumed to represent his experimental apparatus are misleading, but his work was undoubtedly based on experimental measurements and probably largely involved lubricated contacts. Although his work had no influence on the development of the subject over the succeeding centuries, Leonardo da Vinci holds a unique position as a pioneer in tribology.

Keywords

- Sliding friction;

- Rolling friction;

- History of tribology;

- LEONARDO da Vinci

1. Introduction

Although the word ‘tribology’ was first coined almost 450 years after the death of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), it is clear that Leonardo was fully familiar with the basic tribological concepts of friction, lubrication and wear. He has been widely credited with the first quantitative investigations of friction, and with the definition of the two fundamental ‘laws’ of friction some two hundred years before they were enunciated (in 1699) by Guillaume Amontons, with whose name they are now usually associated. These simple statements, which have wide applicability, are:

- •

the force of friction acting between two sliding surfaces is proportional to the load pressing the surfaces together (i.e. the forces have a constant ratio, often called the coefficient of friction), and

- •

the force of friction is independent of the apparent area of contact between the two surfaces.

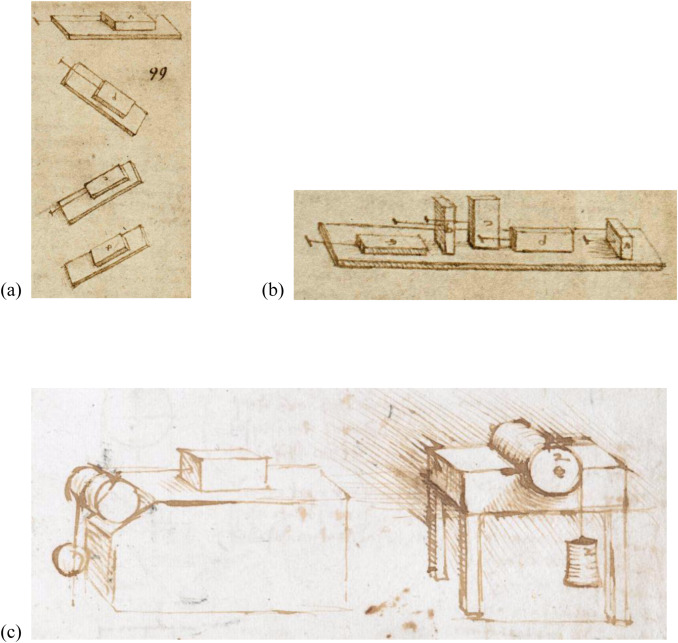

Certain drawings from Leonardo's notebooks have become iconic among tribologists, and have been reproduced widely. These sketches were first brought to the general attention of the community by Dowson [1] in his monumental study of the history of tribology. They show (Fig. 1a) blocks being dragged along planes with various inclinations, (Fig. 1b) a set of similar blocks in different orientations on a horizontal plane, as well as (Fig. 1c) a block resting on a horizontal surface and attached to a string that passes over a cylinder and supports a hanging weight, and a horizontal cylinder lying in a hemicylindrical cavity with a string attached to a hanging weight. However, most researchers in tribology are unaware of the great richness of Leonardo's work in their subject, or of the wider context in which he carried it out. This article aims to explore in detail what Leonardo understood about friction, based on a wide-ranging chronological study of his surviving notebooks. His work on wear will form the basis of a subsequent article.

2. The notebooks

Leonardo's notebooks comprise a diverse collection of writings and sketches with a complex history. The notes in them are almost all written in his distinctive ‘mirror’ writing, from right to left1. He also employed numerous abbreviations and contractions, with no punctuation, and wrote in his native Florentine at a time when Italian spelling and grammar forms were far from standardized. 2

It has been suggested that the more than 6000 pages now known to us may perhaps represent only half, or even a quarter or less of his total output, the rest having been lost [2], [3] and [4]. Over time, many of these separate sheets have been rearranged, rebound and even in some cases dissected into smaller pieces [5]. The various collections (called codices or manuscripts) in their present states are in some cases quite heterogeneous in both subject matter and date. For example, the sheets which make up both the Codex Atlanticus and the Codex Arundel were produced over a period of some 40 years from 1478 to 1518. Some other collections are more uniform in date and topic. Leonardo worked energetically, often on several different subjects and in more than one notebook concurrently, and took little care to arrange his writings thematically or to record dates or places. In some cases, he wrote rough notes in one place, and then used them as the basis for a more polished version elsewhere, either at roughly the same time or much later. For example, much of the material in Codex Madrid I is derived from notes found in the Codex Atlanticus and Paris Manuscripts H, I and M [6]. Some of his drawings are more highly polished than others, allowing one to trace a progressive development from a working sketch to an elegant illustration suitable for a published treatise; but while Leonardo apparently intended eventually to publish much of his work, that never happened. The contents of his notebooks remained largely unknown until the late 19th century (1883) when Jean Paul Richter published transcriptions and English translations of substantial amounts of text with some accompanying sketches [7], although a few extracts had been published before then.

The notebooks themselves, which can now be consulted in facsimile form and also on-line with transcriptions3, present an apparently chaotic and potentially confusing mass of written and diagrammatic material in rough and incomplete note form. On several topics Leonardo repeats himself. As we shall see below, in statements about friction he does this many times. At the beginning of one notebook (the Codex Arundel) he even writes explicitly ‘I fear that before I have completed this I shall have repeated the same thing several times, for which do not blame me, reader, because the subjects are many, and the memory cannot retain them and say, this I will not write because I have already written it. And to avoid this it would be necessary, with every passage I wanted to copy, to read through everything I had already done so as not to replicate it.’ (Arundel 1r, 1508). Any student of his writings quickly becomes aware that Leonardo seldom pauses to reflect on what he has already written: his thoughts are moving far too rapidly, both linearly and tangentially, for that.

The original notebooks are now widely dispersed, although nearly all are in Europe. The collections which contain material relating to tribology are the Codex Atlanticus in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan (cited here as CA), the two Madrid Codices in the Biblioteca Nacional which became lost and were only rediscovered in the mid-1960s (Madrid I and II), the Paris Manuscripts in the Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France (notably MSS A, E, F, G, H, I, L and M), and two collections in London: the Codex Arundel (Arundel) in the British Library and two of the three Forster Codices (Forster II and III) in the Victoria and Albert Museum. There are also a few relevant sheets in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle (Windsor). Pages are conventionally referred to by the number of the folio (leaf) followed by the letter ‘r’ (recto) or ‘v’ (verso)4.

In exploring and evaluating Leonardo's work on tribological topics, one would ideally like to know the dates at which the relevant notes or sketches were produced. This is now possible with reasonable accuracy thanks to the painstaking studies of various scholars, notably Carlo Pedretti who has published chronologies for pages in the Codex Atlanticus [8] and the Codex Arundel [9], and the relevant fragments at Windsor [10]. Dates for the Forster Codices have been taken from Marinoni [11] and for the Madrid Codices from Reti [12], while dates for the other notebooks have been taken from the list provided by Pedretti [6].

Note to users:

Accepted manuscripts are Articles in Press that have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication by the Editorial Board of this publication. They have not yet been copy edited and/or formatted in the publication house style, and may not yet have the full ScienceDirect functionality, e.g., supplementary files may still need to be added, links to references may not resolve yet etc. The text could still change before final publication.

Although accepted manuscripts do not have all bibliographic details available yet, they can already be cited using the year of online publication and the DOI, as follows: author(s), article title, Publication (year), DOI. Please consult the journal's reference style for the exact appearance of these elements, abbreviation of journal names and use of punctuation.

When the final article is assigned to volumes/issues of the Publication, the Article in Press version will be removed and the final version will appear in the associated published volumes/issues of the Publication. The date the article was first made available online will be carried over.