Volume 8: Reviews, Correspondence, and Bibliography.

Book 1: Reviews

Chapter 1: John Venn, The Logic of Chance (Ed.) Review of John Venn's The Logic of Chance, An Essay on the Foundations and Province of the Theory of Probability, with especial Reference to its Application to Moral and Social Science (London and Cambridge, 1866), The North American Review 105 (July 1867) 317-321. This is Peirce's earliest full statement of his theory of probability; cf. 3.19 (1867). His later views are discussed in [CP] II, Book III, and [CP] VII, Book II. †1

1. Here is a book which should be read by every thinking man. Great changes have taken place of late years in the philosophy of chances. Mr. Venn remarks, with great ingenuity and penetration, that this doctrine has had its realistic, conceptualistic, and nominalistic stages. The logic of the Middle Ages is almost coextensive with demonstrative logic; but our age of science opened with a discussion of probable argument (in the Novum Organum), and this part of the subject has given the chief interest to modern studies of logic. What is called the doctrine of chances is, to be sure, but a small part of this field of inquiry; but it is a part where the varieties in the conceptions of probability have been most evident. When this doctrine was first studied, probability seems to have been regarded as something inhering in the singular events, so that it was possible for Bernouilli to enounce it as a theorem (and not merely as an identical proposition), that events happen with frequencies proportional to their probabilities. That was a realistic view. Afterwards it was said that probability does not exist in the singular events, but consists in the degree of credence which ought to be reposed in the occurrence of an event. This is conceptualistic. Finally, probability is regarded as the ratio of the number of events in a certain part of an aggregate of them to the number in the whole aggregate. This is the nominalistic view.

2. This last is the position of Mr. Venn and of the most advanced writers on the subject. The theory was perhaps first put forth by Mr. Stuart Mill; but his head became involved in clouds, and he relapsed into the conceptualistic opinion. Yet the arguments upon the modern side are overwhelming. The question is by no means one of words; but if we were to inquire into the manner in which the terms probable, likely, and so forth, have been used, we should find that they always refer to a determination of a genus of argument. See, for example, Locke on the Understanding, Book IV. ch. 14, §1. There we find it stated that a thing is probable when it is supported by reasons such as lead to a true conclusion. These words such as plainly refer to a genus of argument. Now, what constitutes the validity of a genus of argument? The necessity of thinking the conclusion, say the conceptualists. But a madman may be under a necessity of thinking fallaciously, and (as Bacon suggests) all mankind may be mad after one uniform fashion. Hence the nominalist answers the question thus: A genus of argument is valid when from true premises it will yield a true conclusion — invariably if demonstrative, generally if probable. The conceptualist says, that probability is the degree of credence which ought to be placed in the occurrence of an event. Here is an allusion to an entry on the debtor side of man's ledger. What is this entry? What is the meaning of this ought? Since probability is not an affair of morals, the ought must refer to an alternative to be avoided. Now the reasoner has nothing to fear but error. Probability will accordingly be the degree of credence which it is necessary to repose in a proposition in order to escape error. Conceptualists have not undertaken to say what is meant by "degree of credence." They would probably pronounce it indefinable and indescribable. Their philosophy deals much with the indefinable and indescribable. But propositions are either absolutely true or absolutely false. There is nothing in the facts which corresponds at all to a degree of credence, except that a genus of argument may yield a certain proportion of true conclusions from true premises. Thus, the following form of argument would, in the long run, yield (from true premises) a true conclusion two thirds of the time:—

A is taken at random from among the B's;

2/3 of the B's are C;

∴ A is C.

3. Truth being, then, the agreement of a representation with its object, and there being nothing in re answering to a degree of credence, a modification of a judgment in that respect cannot make it more true, although it may indicate the proportion of such judgments which are true in the long run. That is, indeed, the precise and only use or significance of these fractions termed probabilities: they give security in the long run. Now, in order that the degree of credence should correspond to any truth in the long run, it must be the representation of a general statistical fact, — a real, objective fact. And then, as it is the fact which is said to be probable, and not the belief, the introduction of "degree of credence" at all into the definition of probability is as superfluous as the introduction of a reflection upon a mental process into any other definition would be, — as though we were to define man as "that which (if the essence of the name is to be apprehended) ought to be conceived as a rational animal."

4. To say that the conceptualistic and nominalistic theories are both true at once, is mere ignorance, because their numerical results conflict. A conceptualist might hesitate, perhaps, to say that the probability of a proposition of which he knows absolutely nothing is 1/2, although this would be, in one sense, justifiable for the nominalist, inasmuch as one half of all possible propositions (being contradictions of the other half) are true; but he does not hesitate to assume events to be equally probable when he does not know anything about their probabilities, and this is for the nominalist an utterly unwarrantable procedure. A probability is a statistical fact, and cannot be assumed arbitrarily. Boole first did away with this absurdity, and thereby brought the mathematical doctrine of probabilities into harmony with the modern logical doctrine of probable inference. But Boole (owing to the needs of his calculus) admitted the assumption that simple events whose probabilities are given are independent, — an assumption of the same vicious character. Mr. Venn strikes down this last remnant of conceptualism with a very vigorous hand.

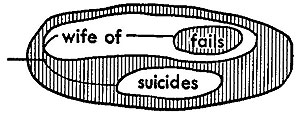

5. He has, however, fallen into some conceptualistic errors of his own; and these are specially manifest in his "applications to moral and social science." The most important of these is contained in the chapter "on the credibility of extraordinary stories"; but it is defended with so much ingenuity as almost to give it the value of a real contribution to science. It is maintained that the credibility of an extraordinary story depends either entirely upon the veracity of the witness, or, in more extraordinary cases, entirely upon the a priori credibility of the story; but that these considerations cannot, under any circumstances, be combined, unless arbitrarily. In order to support this opinion, the author invents an illustration. He supposes that statistics were to have shown that nine out of ten consumptives who go to the island of Madeira live through the first year, and that nine out of ten Englishmen who go to the same island die the first year; what, then, would be the just rate of insurance for the first year of a consumptive Englishman who is about to go to that island? There are no certain data for the least approximation to the proportion of consumptive Englishmen who die in Madeira during the first year. But it is certain that an insurance company which insured only Englishmen in Madeira during the first year, or only consumptives under the same circumstances, would be warranted (a certain moral fact being neglected) in taking the consumptive Englishman at its ordinary rate. Hence, Mr. Venn thinks that an insurance company which insured all sorts of men could with safety and fairness insure the consumptive Englishman either as Englishman or as consumptive. This is an error. For supposing every man to be insured for the same amount, which we may take as our unit of value, and adopting the notation, (c,e) =number of consumptive Englishmen insured. (c,ē) = " " consumptives not English insured. (c̄,e) =" " not consumptive English insured. x = unknown ratio of consumptive English who do not die in the first year. The amount paid out yearly by the company would be, in the long run, 1/10(c,ē) + 9/10(c̄,e) + x(c,e), and x is unknown. This objection to Venn's theory may, however, be waived. †2 Now, the case of an extraordinary story is parallel to this: for such a story is, 1st, told by a certain person, who tells a known proportion of true stories, — say nine out of ten; and, 2d, is of a certain sort (as a fish story), of which a known proportion are true, — say one in ten. Then, as much as before, we come out right, in the long run, by considering such a story under either of the two classes to which it belongs. Hence, says Mr. Venn, we must repose such belief in the story as the veracity of the witness alone, or the antecedent probability alone, requires, or else arbitrarily modify one or other of these degrees of credence. In examining this theory, let us first remark, that there are two principal phrases in which the word probability occurs: for, first, we may speak of the probability of an event or proposition, and then we express ourselves incompletely, inasmuch as we refer to the frequency of true conclusions in the genus of arguments by which the event or proposition in question may have been inferred, without indicating what genus of argument that is; and, secondly, we may speak of the probability that any individual of a certain class has a certain character, when we mean the ratio of the number of those of that class that have that character to the total number in the class. Now it is this latter phrase which we use when we speak of the probability that a story of a certain sort, told by a certain man, is true. And since there is nothing in the data to show what this ratio is, the probability in question is unknown. But a "degree of credence" or "credibility," to be logically determined, must, as we have seen, be an expression of probability in the nominalistic sense; and therefore this "degree of credence" (supposing it to exist) is unknown. "We know not what to believe," is the ordinary and logically correct expression in such cases of perplexity.

6. Credence and expectation cannot be represented by single numbers. Probability is not always known; and then the probability of each degree of probability must enter into the credence. Perhaps this again is not known; then there will be a probability of each degree of probability of each degree of probability; and so on. In the same way, when a risk is run, the expectation is composed of the probabilities of each possible issue, but is not a single number, as the Petersburg problem shows. Suppose the capitalists of the world were to owe me a hundred dollars, and were to offer to pay in either of the following ways: 1st, a coin should be pitched up until it turned up heads (or else a hundred times, if it did not come up heads sooner), and I should be paid two dollars if the head came up the first time, four if the second time, eight if the third time, etc.; or, 2d, a coin should be turned up a hundred times, and I should receive two dollars for every head. Each of these offers would be worth a hundred dollars, in the long run; that is to say, if repeated often enough, I should receive on the average a hundred dollars at each trial. But if the trial were to be made but once, I should infinitely prefer the second alternative, on account of its greater security. Mere certainty is worth a great deal. We wish to know our fate. How much it is worth is a question of political economy. It must go into the market, where its worth is what it will fetch. And since security may be of many kinds (according to the distribution of the probabilities of each sum of money and of each loss, in prospect), the value of the various kinds will fluctuate among one another with the ratio of demand and supply, — the demand varying with the moral and intellectual state of the community, — and thus no single and constant number can represent the value of any kind.

Chapter 2: Fraser's Edition of The Works of George Berkeley (Ed.) Review of Alexander Campbell Fraser's The Works of George Berkeley, D.D., formerly Bishop of Cloyne: including many of his Writings hitherto unpublished, four volumes (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1871), The North American Review 113 (Oct. 1871) 449-472. Cf. Peirce's review of the 1901 edition, [Bibliography] N-1901-10. †1

§1. Introduction

7. This new edition of Berkeley's works is much superior to any of the former ones. It contains some writings not in any of the other editions, and the rest are given with a more carefully edited text. The editor has done his work well. The introductions to the several pieces contain analyses of their contents which will be found of the greatest service to the reader. On the other hand, the explanatory notes which disfigure every page seem to us altogether unnecessary and useless.

8. Berkeley's metaphysical theories have at first sight an air of paradox and levity very unbecoming to a bishop. He denies the existence of matter, our ability to see distance, and the possibility of forming the simplest general conception; while he admits the existence of Platonic ideas; and argues the whole with a cleverness which every reader admits, but which few are convinced by. His disciples seem to think the present moment a favorable one for obtaining for their philosophy a more patient hearing than it has yet got. It is true that we of this day are sceptical and not given to metaphysics, but so, say they, was the generation which Berkeley addressed, and for which his style was chosen; while it is hoped that the spirit of calm and thorough inquiry which is now, for once, almost the fashion, will save the theory from the perverse misrepresentations which formerly assailed it, and lead to a fair examination of the arguments which, in the minds of his sectators, put the truth of it beyond all doubt. But above all, it is anticipated that the Berkeleyan treatment of that question of the validity of human knowledge and of the inductive process of science, which is now so much studied, is such as to command the attention of scientific men to the idealistic system. To us these hopes seem vain. The truth is that the minds from whom the spirit of the age emanates have now no interest in the only problems that metaphysics ever pretended to solve. The abstract acknowledgment of God, Freedom, and Immortality, apart from those other religious beliefs (which cannot possibly rest on metaphysical grounds) which alone may animate this, is now seen to have no practical consequence whatever. The world is getting to think of these creatures of metaphysics, as Aristotle of the Platonic ideas: {teretismata gar esti, kai ei estin, ouden pros ton logon estin}. The question of the grounds of the validity of induction has, it is true, excited an interest, and may continue to do so (though the argument is now become too difficult for popular apprehension); but whatever interest it has had has been due to a hope that the solution of it would afford the basis for sure and useful maxims concerning the logic of induction, — a hope which would be destroyed so soon as it were shown that the question was a purely metaphysical one. This is the prevalent feeling, among advanced minds. It may not be just; but it exists. And its existence is an effectual bar (if there were no other) to the general acceptance of Berkeley's system. The few who do now care for metaphysics are not of that bold order of minds who delight to hold a position so unsheltered by the prejudices of common sense as that of the good bishop.

9. As a matter of history, however, philosophy must always be interesting. It is the best representative of the mental development of each age. It is so even of ours, if we think what really is our philosophy. Metaphysical history is one of the chief branches of history, and ought to be expounded side by side with the history of society, of government, and of war; for in its relations with these we trace the significance of events for the human mind. The history of philosophy in the British Isles is a subject possessing more unity and entirety within itself than has usually been recognized in it. The influence of Descartes was never so great in England as that of traditional conceptions, and we can trace a continuity between modern and mediaeval thought there, which is wanting in the history of France, and still more, if possible, in that of Germany.

10. From very early times, it has been the chief intellectual characteristic of the English to wish to effect everything by the plainest and directest means, without unnecessary contrivance. In war, for example, they rely more than any other people in Europe upon sheer hardihood, and rather despise military science. The main peculiarities of their system of law arise from the fact that every evil has been rectified as it became intolerable, without any thoroughgoing measure. The bill for legalizing marriage with a deceased wife's sister is yearly pressed because it supplies a remedy for an inconvenience actually felt; but nobody has proposed a bill to legalize marriage with a deceased husband's brother. In philosophy, this national tendency appears as a strong preference for the simplest theories, and a resistance to any complication of the theory as long as there is the least possibility that the facts can be explained in the simpler way. And, accordingly, British philosophers have always desired to weed out of philosophy all conceptions which could not be made perfectly definite and easily intelligible, and have shown strong nominalistic tendencies since the time of Edward I., or even earlier. Berkeley is an admirable illustration of this national character, as well as of that strange union of nominalism with Platonism, which has repeatedly appeared in history, and has been such a stumbling-block to the historians of philosophy.

11. The mediaeval metaphysic is so entirely forgotten, and has so close a historic connection with modern English philosophy, and so much bearing upon the truth of Berkeley's doctrine, that we may perhaps be pardoned a few pages on the nature of the celebrated controversy concerning universals. And first let us set down a few dates. It was at the very end of the eleventh century that the dispute concerning nominalism and realism, which had existed in a vague way before, began to attain extraordinary proportions. During the twelfth century it was the matter of most interest to logicians, when William of Champeaux, Abélard, John of Salisbury, Gilbert de la Porrée, and many others, defended as many different opinions. But there was no historic connection between this controversy and those of scholasticism proper, the scholasticism of Aquinas, Scotus, and Ockam. For about the end of the twelfth century a great revolution of thought took place in Europe. What the influences were which produced it requires new historical researches to say. No doubt, it was partly due to the Crusades. But a great awakening of intelligence did take place at that time. It requires, it is true, some examination to distinguish this particular movement from a general awakening which had begun a century earlier, and had been growing ever since. But now there was an accelerated impulse. Commerce was attaining new importance, and was inventing some of her chief conveniences and safeguards. Law, which had hitherto been utterly barbaric, began to be a profession. The civil law was adopted in Europe, the canon law was digested; the common law took some form. The Church, under Innocent III., was assuming the sublime functions of a moderator over kings. And those orders of mendicant friars were established, two of which did so much for the development of the scholastic philosophy. Art felt the spirit of a new age, and there could hardly be a greater change than from the highly ornate round-arched architecture of the twelfth century to the comparatively simple Gothic of the thirteenth. Indeed, if any one wishes to know what a scholastic commentary is like, and what the tone of thought in it is, he has only to contemplate a Gothic cathedral. The first quality of either is a religious devotion, truly heroic. One feels that the men who did these works did really believe in religion as we believe in nothing. We cannot easily understand how Thomas Aquinas can speculate so much on the nature of angels, and whether ten thousand of them could dance on a needle's point. But it was simply because he held them for real. If they are real, why are they not more interesting than the bewildering varieties of insects which naturalists study; or why should the orbits of double stars attract more attention than spiritual intelligences? It will be said that we have no means of knowing anything about them. But that is on a par with censuring the schoolmen for referring questions to the authority of the Bible and of the Church. If they really believed in their religion, as they did, what better could they do? And if they found in these authorities testimony concerning angels, how could they avoid admitting it. Indeed, objections of this sort only make it appear still more clearly how much those were the ages of faith. And if the spirit was not altogether admirable, it is only because faith itself has its faults as a foundation for the intellectual character. The men of that time did fully believe and did think that, for the sake of giving themselves up absolutely to their great task of building or of writing, it was well worth while to resign all the joys of life. Think of the spirit in which Duns Scotus must have worked, who wrote his thirteen volumes in folio, in a style as condensed as the most condensed parts of Aristotle, before the age of thirty-four. Nothing is more striking in either of the great intellectual products of that age, than the complete absence of self-conceit on the part of the artist or philosopher. That anything of value can be added to his sacred and catholic work by its having the smack of individuality about it, is what he has never conceived. His work is not designed to embody his ideas, but the universal truth; there will not be one thing in it however minute, for which you will not find that he has his authority; and whatever originality emerges is of that inborn kind which so saturates a man that he cannot himself perceive it. The individual feels his own worthlessness in comparison with his task, and does not dare to introduce his vanity into the doing of it. Then there is no machine-work, no unthinking repetition about the thing. Every part is worked out for itself as a separate problem, no matter how analogous it may be in general to another part. And no matter how small and hidden a detail may be, it has been conscientiously studied, as though it were intended for the eye of God. Allied to this character is a detestation of antithesis or the studied balancing of one thing against another, and of a too geometrical grouping, — a hatred of posing which is as much a moral trait as the others. Finally, there is nothing in which the scholastic philosophy and the Gothic architecture resemble one another more than in the gradually increasing sense of immensity which impresses the mind of the student as he learns to appreciate the real dimensions and cost of each. It is very unfortunate that the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries should, under the name of Middle Ages, be confounded with others, which they are in every respect as unlike as the Renaissance is from modern times. In the history of logic, the break between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries is so great that only one author of the former age is ever quoted in the latter. If this is to be attributed to the fuller acquaintance with the works of Aristotle, to what, we would ask, is this profounder study itself to be attributed, since it is now known that the knowledge of those works was not imported from the Arabs? The thirteenth century was realistic, but the question concerning universals was not as much agitated as several others. Until about the end of the century, scholasticism was somewhat vague, immature, and unconscious of its own power. Its greatest glory was in the first half of the fourteenth century. Then Duns Scotus, Died 1308. †2 a Briton (for whether Scotch, Irish, or English is disputed), first stated the realistic position consistently, and developed it with great fulness and applied it to all the different questions which depend upon it. His theory of "formalities" was the subtlest, except perhaps Hegel's logic, ever broached, and he was separated from nominalism only by the division of a hair. It is not therefore surprising that the nominalistic position was soon adopted by several writers, especially by the celebrated William of Ockam, who took the lead of this party by the thoroughgoing and masterly way in which he treated the theory and combined it with a then rather recent but now forgotten addition to the doctrine of logical terms. With Ockam, who died in 1347, scholasticism may be said to have culminated. After him the scholastic philosophy showed a tendency to separate itself from the religious element which alone could dignify it, and sunk first into extreme formalism and fancifulness, and then into the merited contempt of all men; just as the Gothic architecture had a very similar fate, at about the same time, and for much the same reasons.

§2. Formulation of Realism

12. The current explanations of the realist-nominalist controversy are equally false and unintelligible. They are said to be derived ultimately from Bayle's Dictionary; at any rate, they are not based on a study of the authors. "Few, very few, for a hundred years past," says Hallam, with truth, "have broken the repose of the immense works of the schoolmen." Yet it is perfectly possible so to state the matter that no one shall fail to comprehend what the question was, and how there might be two opinions about it. Are universals real? We have only to stop and consider a moment what was meant by the word real, when the whole issue soon becomes apparent. Objects are divided into figments, dreams, etc., on the one hand, and realities on the other. The former are those which exist only inasmuch as you or I or some man imagines them; the latter are those which have an existence independent of your mind or mine or that of any number of persons. The real is that which is not whatever we happen to think it, but is unaffected by what we may think of it. (Ed.) Cf. 5.311. †3 The question, therefore, is whether man, horse, and other names of natural classes, correspond with anything which all men, or all horses, really have in common, independent of our thought, or whether these classes are constituted simply by a likeness in the way in which our minds are affected by individual objects which have in themselves no resemblance or relationship whatsoever. Now that this is a real question which different minds will naturally answer in opposite ways, becomes clear when we think that there are two widely separated points of view, from which reality, as just defined, may be regarded. Where is the real, the thing independent of how we think it, to be found? There must be such a thing, for we find our opinions constrained; there is something, therefore, which influences our thoughts, and is not created by them. We have, it is true, nothing immediately present to us but thoughts. These thoughts, however, have been caused by sensations, and those sensations are constrained by something out of the mind. This thing out of the mind, which directly influences sensation, and through sensation thought, because it is out of the mind, is independent of how we think it, and is, in short, the real. Here is one view of reality, a very familiar one. And from this point of view it is clear that the nominalistic answer must be given to the question concerning universals. For, while from this standpoint it may be admitted to be true as a rough statement that one man is like another, the exact sense being that the realities external to the mind produce sensations which may be embraced under one conception, yet it can by no means be admitted that the two real men have really anything in common, for to say that they are both men is only to say that the one mental term or thought-sign "man" stands indifferently for either of the sensible objects caused by the two external realities; so that not even the two sensations have in themselves anything in common, and far less is it to be inferred that the external realities have. This conception of reality is so familiar, that it is unnecessary to dwell upon it; but the other, or realist conception, if less familiar, is even more natural and obvious. All human thought and opinion contains an arbitrary, accidental element, dependent on the limitations in circumstances, power, and bent of the individual; an element of error, in short. But human opinion universally tends in the long run to a definite form, which is the truth. Let any human being have enough information and exert enough thought upon any question, and the result will be that he will arrive at a certain definite conclusion, which is the same that any other mind will reach under sufficiently favorable circumstances. Suppose two men, one deaf, the other blind. One hears a man declare he means to kill another, hears the report of the pistol, and hears the victim cry; the other sees the murder done. Their sensations are affected in the highest degree with their individual peculiarities. The first information that their sensations will give them, their first inferences, will be more nearly alike, but still different; the one having, for example, the idea of a man shouting, the other of a man with a threatening aspect; but their final conclusions, the thought the remotest from sense, will be identical and free from the one-sidedness of their idiosyncrasies. There is, then, to every question a true answer, a final conclusion, to which the opinion of every man is constantly gravitating. He may for a time recede from it, but give him more experience and time for consideration, and he will finally approach it. The individual may not live to reach the truth; there is a residuum of error in every individual's opinions. No matter; it remains that there is a definite opinion to which the mind of man is, on the whole and in the long run, tending. On many questions the final agreement is already reached, on all it will be reached if time enough is given. The arbitrary will or other individual peculiarities of a sufficiently large number of minds may postpone the general agreement in that opinion indefinitely; but it cannot affect what the character of that opinion shall be when it is reached. This final opinion, then, is independent, not indeed of thought in general, but of all that is arbitrary and individual in thought; is quite independent of how you, or I, or any number of men think. (Ed.) Cf. 5.311. †4 Everything, therefore, which will be thought to exist in the final opinion is real, and nothing else. What is the POWER of external things, to affect the senses? To say that people sleep after taking opium because it has a soporific power, is that to say anything in the world but that people sleep after taking opium because they sleep after taking opium? To assert the existence of a power or potency, is it to assert the existence of anything actual? Or to say that a thing has a potential existence, is it to say that it has an actual existence? In other words, is the present existence of a power anything in the world but a regularity in future events relating to a certain thing regarded as an element which is to be taken account of beforehand, in the conception of that thing? If not, to assert that there are external things which can be known only as exerting a power on our sense, is nothing different from asserting that there is a general drift in the history of human thought which will lead it to one general agreement, one catholic consent. And any truth more perfect than this destined conclusion, any reality more absolute than what is thought in it, is a fiction of metaphysics. It is obvious how this way of thinking harmonizes with a belief in an infallible Church, and how much more natural it would be in the Middle Ages than in Protestant or positivist times.

13. This theory of reality is instantly fatal to the idea of a thing in itself, — a thing existing independent of all relation to the mind's conception of it. Yet it would by no means forbid, but rather encourage us, to regard the appearances of sense as only signs of the realities. Only, the realities which they represent would not be the unknowable cause of sensation, but noumena, or intelligible conceptions which are the last products of the mental action which is set in motion by sensation. The matter of sensation is altogether accidental; precisely the same information, practically, being capable of communication through different senses. And the catholic consent which constitutes the truth is by no means to be limited to men in this earthly life or to the human race, but extends to the whole communion of minds to which we belong, including some probably whose senses are very different from ours, so that in that consent no predication of a sensible quality can enter, except as an admission that so certain sorts of senses are affected. This theory is also highly favorable to a belief in external realities. It will, to be sure, deny that there is any reality which is absolutely incognizable in itself, so that it cannot be taken into the mind. But observing that "the external" means simply that which is independent of what phenomenon is immediately present, that is of how we may think or feel; just as "the real" means that which is independent of how we may think or feel about it; it must be granted that there are many objects of true science which are external, because there are many objects of thought which, if they are independent of that thinking whereby they are thought (that is, if they are real), are indisputably independent of all other thoughts and feelings.

14. It is plain that this view of reality is inevitably realistic; because general conceptions enter into all judgments, and therefore into true opinions. Consequently a thing in the general is as real as in the concrete. It is perfectly true that all white things have whiteness in them, for that is only saying, in another form of words, that all white things are white; but since it is true that real things possess whiteness, whiteness is real. It is a real which only exists by virtue of an act of thought knowing it, but that thought is not an arbitrary or accidental one dependent on any idiosyncrasies, but one which will hold in the final opinion.

15. This theory involves a phenomenalism. But it is the phenomenalism of Kant, and not that of Hume. Indeed, what Kant called his Copernican step was precisely the passage from the nominalistic to the realistic view of reality. It was the essence of his philosophy to regard the real object as determined by the mind. That was nothing else than to consider every conception and intuition which enters necessarily into the experience of an object, and which is not transitory and accidental, as having objective validity. In short, it was to regard the reality as the normal product of mental action, and not as the incognizable cause of it.

16. This realistic theory is thus a highly practical and common-sense position. Wherever universal agreement prevails, the realist will not be the one to disturb the general belief by idle and fictitious doubts. For according to him it is a consensus or common confession which constitutes reality. What he wants, therefore, is to see questions put to rest. And if a general belief, which is perfectly stable and immovable, can in any way be produced, though it be by the fagot and the rack, to talk of any error in such belief is utterly absurd. The realist will hold that the very same objects which are immediately present in our minds in experience really exist just as they are experienced out of the mind; that is, he will maintain a doctrine of immediate perception. He will not, therefore, sunder existence out of the mind and being in the mind as two wholly improportionable modes. When a thing is in such relation to the individual mind that that mind cognizes it, it is in the mind; and its being so in the mind will not in the least diminish its external existence. For he does not think of the mind as a receptacle, which if a thing is in, it ceases to be out of. To make a distinction between the true conception of a thing and the thing itself is, he will say, only to regard one and the same thing from two different points of view; for the immediate object of thought in a true judgment is the reality. The realist will, therefore, believe in the objectivity of all necessary conceptions, space, time, relation, cause, and the like.

17. No realist or nominalist ever expressed so definitely, perhaps, as is here done, his conception of reality. It is difficult to give a clear notion of an opinion of a past age, without exaggerating its distinctness. But careful examination of the works of the schoolmen will show that the distinction between these two views of the real — one as the fountain of the current of human thought, the other as the unmoving form to which it is flowing — is what really occasions their disagreement on the question concerning universals. The gist of all the nominalist's arguments will be found to relate to a res extra animam, while the realist defends his position only by assuming that the immediate object of thought in a true judgment is real. The notion that the controversy between realism and nominalism had anything to do with Platonic ideas is a mere product of the imagination, which the slightest examination of the books would suffice to disprove. But to prove that the statement here given of the essence of these positions is historically true and not a fancy sketch, it will be well to add a brief analysis of the opinions of Scotus and Ockam.

§3. Scotus, Ockam, and Hobbes

18. Scotus sees several questions confounded together under the usual utrum universale est aliquid in rebus. In the first place, there is the question concerning the Platonic forms. But putting Platonism aside as at least incapable of proof, and as a self-contradictory opinion if the archetypes are supposed to be strictly universal, there is the celebrated dispute among Aristotelians as to whether the universal is really in things or only derives its existence from the mind. Universality is a relation of a predicate to the subjects of which it is predicated. That can exist only in the mind, wherein alone the coupling of subject and predicate takes place. But the word universal is also used to denote what are named by such terms as a man or a horse; these are called universals, because a man is not necessarily this man, nor a horse this horse. In such a sense it is plain universals are real; there really is a man and there really is a horse. The whole difficulty is with the actually indeterminate universal, that which not only is not necessarily this, but which, being one single object of thought, is predicable of many things. In regard to this it may be asked, first, is it necessary to its existence that it should be in the mind; and, second, does it exist in re? There are two ways in which a thing may be in the mind, — habitualiter and actualiter. A notion is in the mind actualiter when it is actually conceived; it is in the mind habitualiter when it can directly produce a conception. It is by virtue of mental association (we moderns should say), that things are in the mind habitualiter. In the Aristotelian philosophy, the intellect is regarded as being to the soul what the eye is to the body. The mind perceives likenesses and other relations in the objects of sense, and thus just as sense affords sensible images of things, so the intellect affords intelligible images of them. It is as such a species intelligibilis that Scotus supposes that a conception exists which is in the mind habitualiter, not actualiter. This species is in the mind, in the sense of being the immediate object of knowledge, but its existence in the mind is independent of consciousness. Now that the actual cognition of the universal is necessary to its existence, Scotus denies. The subject of science is universal; and if the existence of [the] universal were dependent upon what we happened to be thinking, science would not relate to anything real. On the other hand, he admits that the universal must be in the mind habitualiter, so that if a thing be considered as it is independent of its being cognized, there is no universality in it. For there is in re extra no one intelligible object attributed to different things. He holds, therefore, that such natures (i.e. sorts of things) as a man and a horse, which are real, and are not of themselves necessarily this man or this horse, though they cannot exist in re without being some particular man or horse, are in the species intelligibilis always represented positively indeterminate, it being the nature of the mind so to represent things. Accordingly any such nature is to be regarded as something which is of itself neither universal nor singular, but is universal in the mind, singular in things out of the mind. If there were nothing in the different men or horses which was not of itself singular, there would be no real unity except the numerical unity of the singulars; which would involve such absurd consequences as that the only real difference would be a numerical difference, and that there would be no real likenesses among things. If, therefore, it is asked whether the universal is in things, the answer is, that the nature which in the mind is universal, and is not in itself singular, exists in things. It is the very same nature which in the mind is universal and in re is singular; for if it were not, in knowing anything of a universal we should be knowing nothing of things, but only of our own thoughts, and our opinion would not be converted from true to false by a change in things. This nature is actually indeterminate only so far as it is in the mind. But to say that an object is in the mind is only a metaphorical way of saying that it stands to the intellect in the relation of known to knower. The truth is, therefore, that that real nature which exists in re, apart from all action of the intellect, though in itself, apart from its relations, it be singular, yet is actually universal as it exists in relation to the mind. But this universal only differs from the singular in the manner of its being conceived (formaliter), but not in the manner of its existence (realiter).

19. Though this is the slightest possible sketch of the realism of Scotus, and leaves a number of important points unnoticed, yet it is sufficient to show the general manner of his thought and how subtle and difficult his doctrine is. That about one and the same nature being in the grade of singularity in existence, and in the grade of universality in the mind, gave rise to an extensive doctrine concerning the various kinds of identity and difference, called the doctrine of the formalitates; and this is the point against which Ockam directed his attack.

20. Ockam's nominalism may be said to be the next stage in English opinion. As Scotus's mind is always running on forms, so Ockam's is on logical terms; and all the subtle distinctions which Scotus effects by his formalitates, Ockam explains by implied syncategorematics (or adverbial expressions, such as per se, etc.) in terms. Ockam always thinks of a mental conception as a logical term, which, instead of existing on paper, or in the voice, is in the mind, but is of the same general nature, namely, a sign. The conception and the word differ in two respects: first, a word is arbitrarily imposed, while a conception is a natural sign; second, a word signifies whatever it signifies only indirectly, through the conception which signifies the same thing directly. Ockam enunciates his nominalism as follows: "It should be known that singular may be taken in two senses. In one sense, it signifies that which is one and not many; and in this sense those who hold that the universal is a quality of mind predicable of many, standing however in this predication, not for itself, but for those many (i.e. the nominalists), have to say that every universal is truly and really singular; because as every word, however general we may agree to consider it, is truly and really singular and one in number, because it is one and not many, so every universal is singular. In another sense, the name singular is used to denote whatever is one and not many, is a sign of something which is singular in the first sense, and is not fit to be the sign of many. Whence, using the word universal for that which is not one in number, — an acceptation many attribute to it, — I say that there is no universal; unless perchance you abuse the word and say that people is not one in number and is universal. But that would be puerile. It is to be maintained, therefore, that every universal is one singular thing, and therefore there is no universal except by signification, that is, by its being the sign of many." (Ed.) See William Ockham, Summa Logicae, Pars Prima, Philotheus Boehner, ed., St. Bonaventure, New York, 1951, p. 44; cf. Ernest A. Moody, The Logic of William of Ockham, Sheed and Ward, Inc., New York, 1935, footnotes pp. 81-82, for a somewhat different version of this passage. †5 The arguments by which he supports this position present nothing of interest. The entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem is the argument of Durand de St. Pourcain. But any given piece of popular information about scholasticism may be safely assumed to be wrong. †6 Against Scotus's doctrine that universals are without the mind in individuals, but are not really distinct from the individuals, but only formally so, he objects that it is impossible there should be any distinction existing out of the mind except between things really distinct. Yet he does not think of denying that an individual consists of matter and form, for these, though inseparable, are really distinct things; though a modern nominalist might ask in what sense things could be said to be distinct independently of any action of the mind, which are so inseparable as matter and form. But as to relation, he most emphatically and clearly denies that it exists as anything different from the things related; and this denial he expressly extends to relations of agreement and likeness as well as to those of opposition. While, therefore, he admits the real existence of qualities, he denies that these real qualities are respects in which things agree or differ; but things which agree or differ agree or differ in themselves and in no respect extra animam. He allows that things without the mind are similar, but this similarity consists merely in the fact that the mind can abstract one notion from the contemplation of them. A resemblance, therefore, consists solely in the property of the mind by which it naturally imposes one mental sign upon the resembling things. Yet he allows there is something in the things to which this mental sign corresponds.

21. This is the nominalism of Ockam so far as it can be sketched in a single paragraph, and without entering into the complexities of the Aristotelian psychology nor of the parva logicalia. He is not so thoroughgoing as he might be, yet compared with Durandus and other contemporary nominalists he seems very radical and profound. He is truly the venerabilis inceptor of a new way of philosophizing which has now broadened, perhaps deepened also, into English empiricism.

22. England never forgot these teachings. During that Renaissance period when men could think that human knowledge was to be advanced by the use of Cicero's Commonplaces, we naturally see little effect from them; but one of the earliest prominent figures in modern philosophy is a man who carried the nominalistic spirit into everything — religion, ethics, psychology, and physics, the plusquam nominalis, Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury. His razor cuts off, not merely substantial forms, but every incorporeal substance. As for universals, he not only denies their real existence, but even that there are any universal conceptions except so far as we conceive names. In every part of his logic, names and speech play an extraordinarily important part. Truth and falsity, he says, have no place but among such creatures as use speech, for a true proposition is simply one whose predicate is the name of everything of which the subject is the name. "From hence, also, this may be deduced, that the first truths were arbitrarily made by those that first of all imposed names upon things, or received them from the imposition of others. For it is true (for example), that man is a living creature, but it is for this reason that it pleased men to impose both those names on the same thing." (Ed.) The English Works of Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury, Sir William Molesworth, ed., Vol. I, London, 1839, p. 36. †7 The difference between true religion and superstition is simply that the state recognizes the former and not the latter.

23. The nominalistic love of simple theories is seen also in his opinion, that every event is a movement, and that the sensible qualities exist only in sensible beings, and in his doctrine that man is at bottom purely selfish in his actions.

24. His views concerning matter are worthy of notice, because Berkeley is known to have been a student of Hobbes, as Hobbes confesses himself to have been of Ockam. The following paragraph gives his opinion:—

"And as for that matter which is common to all things, and which philosophers, following Aristotle, usually call materia prima, that is, first matter, it is not a body distinct from all other bodies, nor is it one of them. What then is it? A mere name; yet a name which is not of vain use; for it signifies a conception of body without the consideration of any form or other accident except only magnitude or extension, and aptness to receive form and other accident. So that whensoever we have use of the name body in general, if we use that of materia prima, we do well. For when a man, not knowing which was first, water or ice, would find out which of the two were the matter of both, he would be fain to suppose some third matter which were neither of these two; so he that would find out what is the matter of all things ought to suppose such as is not the matter of anything that exists. Wherefore materia prima is nothing; and therefore they do not attribute to it form or any other accident, besides quantity; whereas all singular things have their forms and accidents certain.

"Materia prima therefore is body in general, that is, body considered universally, not as having neither form nor any accident, but in which no form nor any other accident but quantity are at all considered, that is, they are not drawn into argumentation." — p. 118. (Ed.) The English Works of Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury, Sir William Molesworth, ed., Vol. I, London, 1839, pp. 118-119. †8

25. The next great name in English philosophy is Locke's. His philosophy is nominalistic, but does not regard things from a logical point of view at all. Nominalism, however, appears in psychology as sensationalism; for nominalism arises from taking that view of reality which regards whatever is in thought as caused by something in sense, and whatever is in sense as caused by something without the mind. But everybody knows that this is the character of Locke's philosophy. He believed that every idea springs from sensation and from his (vaguely explained) reflection.

§4. Berkeley's Philosophy

26. Berkeley is undoubtedly more the offspring of Locke than of any other philosopher. Yet the influence of Hobbes with him is very evident and great; and Malebranche doubtless contributed to his thought. But he was by nature a radical and a nominalist. His whole philosophy rests upon an extreme nominalism of a sensationalistic type. He sets out with the proposition (supposed to have been already proved by Locke), that all the ideas in our minds are simply reproductions of sensations, external and internal. He maintains, moreover, that sensations can only be thus reproduced in such combinations as might have been given in immediate perception. We can conceive a man without a head, because there is nothing in the nature of sense to prevent our seeing such a thing; but we cannot conceive a sound without any pitch, because the two things are necessarily united in perception. On this principle he denies that we can have any abstract general ideas, that is, that universals can exist in the mind; if I think of a man it must be either of a short or a long or a middle-sized man, because if I see a man he must be one or the other of these. In the first draft of the Introduction of the Principles of Human Knowledge, which is now for the first time printed, he even goes so far as to censure Ockam for admitting that we can have general terms in our mind; Ockam's opinion being that we have in our minds conceptions, which are singular themselves, but are signs of many things. The sole difference between Ockam and Hobbes is that the former admits the universal signs in the mind to be natural, while the latter thinks they only follow instituted language. The consequence of this difference is that, while Ockam regards all truth as depending on the mind's naturally imposing the same sign on two things, Hobbes will have it that the first truths were established by convention. But both would doubtless allow that there is something in re to which such truths corresponded. But the sense of Berkeley's implication would be that there are no universal thought-signs at all. Whence it would follow that there is no truth and no judgments but propositions spoken or on paper. †9 But Berkeley probably knew only of Ockam from hearsay, and perhaps thought he occupied a position like that of Locke. Locke had a very singular opinion on the subject of general conceptions. He says:—

"If we nicely reflect upon them, we shall find that general ideas are fictions, and contrivances of the mind, that carry difficulty with them, and do not so easily offer themselves as we are apt to imagine. For example, does it not require some pains and skill to form the general idea of a triangle (which is none of the most abstract, comprehensive, and difficult); for it must be neither oblique nor rectangle, neither equilateral, equicrural, nor scalenon, but all and none of these at once? In effect, is something imperfect that cannot exist, an idea wherein some parts of several different and inconsistent ideas are put together." (Ed.) See An Essay Concerning Human Understanding by John Locke, edited by Alexander Campbell Fraser, Vol. II, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1894, p. 247, §9. †10

27. To this Berkeley replies:—

"Much is here said of the difficulty that abstract ideas carry with them, and the pains and skill requisite in forming them. And it is on all hands agreed that there is need of great toil and labor of the mind to emancipate our thoughts from particular objects, and raise them to those sublime speculations that are conversant about abstract ideas. From all which the natural consequence should seem to be, that so difficult a thing as the forming of abstract ideas was not necessary to communication, which is so easy and familiar to all sort of men. But we are told, if they seem obvious and easy to grown men, it is only because by constant and familiar use they are made so. Now, I would fain know at what time it is men are employed in surmounting that difficulty [and furnishing themselves with those necessary helps for discourse]. It cannot be when they are grown up, for then it seems they are not conscious of such painstaking; it remains, therefore, to be the business of their childhood. And surely the great and multiplied labor of framing abstract notions will be found a hard task at that tender age. Is it not a hard thing to imagine that a couple of children cannot prate together of their sugar-plums and rattles, and the rest of their little trinkets, till they have first tacked together numberless inconsistencies, and so formed in their minds abstract general ideas, and annexed them to every common name they make use of?" (Ed.) In the work under review this passage from the introduction to "A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge" is to be found in Vol. I, p. 146, §14. The portion in brackets was omitted by Peirce without notice. †11

28. In his private note-book Berkeley has the following:— "Mem. To bring the killing blow at the last, e.g. in the matter of abstraction to bring Locke's general triangle in the last." (Ed.) In the work under review this passage is in "Commonplace Book of Occasional Metaphysical Thoughts," Vol. IV, p. 448. †12

There was certainly an opportunity for a splendid blow here, and he gave it.

29. From this nominalism he deduces his idealistic doctrine. And he puts it beyond any doubt that, if this principle be admitted, the existence of matter must be denied. Nothing that we can know or even think can exist without the mind, for we can only think reproductions of sensations, and the esse of these is percipi. To put it another way, we cannot think of a thing as existing unperceived, for we cannot separate in thought what cannot be separated in perception. It is true, I can think of a tree in a park without anybody by to see it; but I cannot think of it without anybody to imagine it; for I am aware that I am imagining it all the time. Syllogistically: trees, mountains, rivers, and all sensible things are perceived; and anything which is perceived is a sensation; now for a sensation to exist without being perceived is impossible; therefore, for any sensible thing to exist out of perception is impossible. Nor can there be anything out of the mind which resembles a sensible object, for the conception of likeness cannot be separated from likeness between ideas, because that is the only likeness which can be given in perception. An idea can be nothing but an idea, and it is absurd to say that anything inaudible can resemble a sound, or that anything invisible can resemble a color. But what exists without the mind can neither be heard nor seen; for we perceive only sensations within the mind. It is said that Matter exists without the mind. But what is meant by matter? It is acknowledged to be known only as supporting the accidents of bodies; and this word 'supporting' in this connection is a word without meaning. Nor is there any necessity for the hypothesis of external bodies. What we observe is that we have ideas. Were there any use in supposing external things it would be to account for this fact. But grant that bodies exist, and no one can say how they can possibly affect the mind; so that instead of removing a difficulty, the hypothesis only makes a new one.

30. But though Berkeley thinks we know nothing out of the mind, he by no means holds that all our experience is of a merely phantasmagoric character. It is not all a dream; for there are two things which distinguish experience from imagination: one is the superior vividness of experience; the other and most important is its connected character. Its parts hang together in the most intimate and intricate conjunction, in consequence of which we can infer the future from the past. "These two things it is," says Berkeley, in effect, "which constitute reality. I do not, therefore, deny the reality of common experience, although I deny its externality." Here we seem to have a third new conception of reality, different from either of those which we have insisted are characteristic of the nominalist and realist respectively, or if this is to be identified with either of those, it is with the realist view. Is not this something quite unexpected from so extreme a nominalist? To us, at least, it seems that this conception is indeed required to give an air of common sense to Berkeley's theory, but that it is of a totally different complexion from the rest. It seems to be something imported into his philosophy from without. We shall glance at this point again presently. He goes on to say that ideas are perfectly inert and passive. One idea does not make another and there is no power or agency in it. Hence, as there must be some cause of the succession of ideas, it must be Spirit. There is no idea of a spirit. But I have a consciousness of the operations of my spirit, what he calls a notion of my activity in calling up ideas at pleasure, and so have a relative knowledge of myself as an active being. But there is a succession of ideas not dependent on my will, the ideas of perception. Real things do not depend on my thought, but have an existence distinct from being perceived by me; but the esse of everything is percipi; therefore, there must be some other mind wherein they exist. "As sure, therefore, as the sensible world really exists, so sure do there an infinite omnipotent Spirit who contains and supports it." (Ed.) In the work reviewed this passage from "The Second Dialogue between Hylas and Philonous" is in Vol. I, p. 304. There the passage reads: "As sure, therefore, as the sensible world really exists, so sure is there an infinite omnipresent Spirit, who contains and supports it." †13 This puts the keystone into the arch of Berkeleyan idealism, and gives a theory of the relation of the mind to external nature which, compared with the Cartesian Divine Assistance, is very satisfactory. It has been well remarked that, if the Cartesian dualism be admitted, no divine assistance can enable things to affect the mind or the mind things, but divine power must do the whole work. Berkeley's philosophy, like so many others, has partly originated in an attempt to escape the inconveniences of the Cartesian dualism. God, who has created our spirits, has the power immediately to raise ideas in them; and out of his wisdom and benevolence, he does this with such regularity that these ideas may serve as signs of one another. Hence, the laws of nature. Berkeley does not explain how our wills act on our bodies, but perhaps he would say that to a certain limited extent we can produce ideas in the mind of God as he does in ours. But a material thing being only an idea, exists only so long as it is in some mind. Should every mind cease to think it for a while, for so long it ceases to exist. Its permanent existence is kept up by its being an idea in the mind of God. Here we see how superficially the just-mentioned theory of reality is laid over the body of his thought. If the reality of a thing consists in its harmony with the body of realities, it is a quite needless extravagance to say that it ceases to exist as soon as it is no longer thought of. For the coherence of an idea with experience in general does not depend at all upon its being actually present to the mind all the time. But it is clear that when Berkeley says that reality consists in the connection of experience, he is simply using the word reality in a sense of his own. That an object's independence of our thought about it is constituted by its connection with experience in general, he has never conceived. On the contrary, that, according to him, is effected by its being in the mind of God. In the usual sense of the word reality, therefore, Berkeley's doctrine is that the reality of sensible things resides only in their archetypes in the divine mind. This is Platonistic, but it is not realistic. On the contrary, since it places reality wholly out of the mind in the cause of sensations, and since it denies reality (in the true sense of the word) to sensible things in so far as they are sensible, it is distinctly nominalistic. Historically there have been prominent examples of an alliance between nominalism and Platonism. Abélard and John of Salisbury, the only two defenders of nominalism of the time of the great controversy whose works remain to us, are both Platonists; and Roscellin, the famous author of the sententia de flatu vocis, the first man in the Middle Ages who carried attention to nominalism, is said and believed (all his writings are lost) to have been a follower of Scotus Erigena, the great Platonist of the ninth century. The reason of this odd conjunction of doctrines may perhaps be guessed at. The nominalist, by isolating his reality so entirely from mental influence as he has done, has made it something which the mind cannot conceive; he has created the so often talked of "improportion between the mind and the thing in itself." And it is to overcome the various difficulties to which this gives rise, that he supposes this noumenon, which, being totally unknown, the imagination can play about as it pleases, to be the emanation of archetypal ideas. The reality thus receives an intelligible nature again, and the peculiar inconveniences of nominalism are to some degree avoided.

31. It does not seem to us strange that Berkeley's idealistic writings have not been received with much favor. They contain a great deal of argumentation of doubtful soundness, the dazzling character of which puts us more on our guard against it. They appear to be the productions of a most brilliant, original, powerful, but not thoroughly disciplined mind. He is apt to set out with wildly radical propositions, which he qualifies when they lead him to consequences he is not prepared to accept, without seeing how great the importance of his admissions is. He plainly begins his principles of human knowledge with the assumption that we have nothing in our minds but sensations, external and internal, and reproductions of them in the imagination. This goes far beyond Locke; it can be maintained only by the help of that "mental chemistry" started by Hartley. But soon we find him admitting various notions which are not ideas, or reproductions of sensations, the most striking of which is the notion of a cause, which he leaves himself no way of accounting for experientially. Again, he lays down the principle that we can have no ideas in which the sensations are reproduced in an order or combination different from what could have occurred in experience; and that therefore we have no abstract conceptions. But he very soon grants that we can consider a triangle, without attending to whether it is equilateral, isosceles, or scalene; and does not reflect that such exclusive attention constitutes a species of abstraction. His want of profound study is also shown in his so wholly mistaking, as he does, the function of the hypothesis of matter. He thinks its only purpose is to account for the production of ideas in our minds, so occupied is he with the Cartesian problem. But the real part that material substance has to play is to account for (or formulate) the constant connection between the accidents. In his theory, this office is performed by the wisdom and benevolence of God in exciting ideas with such regularity that we can know what to expect. This makes the unity of accidents a rational unity, the material theory makes it a unity not of a directly intellectual origin. The question is, then, which does experience, which does science decide for? Does it appear that in nature all regularities are directly rational, all causes final causes; or does it appear that regularities extend beyond the requirement of a rational purpose, and are brought about by mechanical causes. Now science, as we all know, is generally hostile to the final causes, the operation of which it would restrict within certain spheres, and it finds decidedly an other than directly intellectual regularity in the universe. Accordingly the claim which Mr. Collyns Simon, Professor Fraser, and Mr. Archer Butler make for Berkeleyanism, that it is especially fit to harmonize with scientific thought, is as far as possible from the truth. The sort of science that his idealism would foster would be one which should consist in saying what each natural production was made for. Berkeley's own remarks about natural philosophy show how little he sympathized with physicists. They should all be read; we have only room to quote a detached sentence or two:—

"To endeavor to explain the production of colors or sound by figure, motion, magnitude, and the like, must needs be labor in vain . . . . In the business of gravitation or mutual attraction, because it appears in many instances, some are straightway for pronouncing it universal; and that to attract and be attracted by every body is an essential quality inherent in all bodies whatever . . . . There is nothing necessary or essential in the case, but it depends entirely on the will of the Governing Spirit, who causes certain bodies to cleave together or tend towards each other according to various laws, whilst he keeps others at a fixed distance; and to some he gives a quite contrary tendency, to fly asunder just as he sees convenient . . . . First, it is plain philosophers amuse themselves in vain, when they inquire for any natural efficient cause, distinct from mind or spirit. Secondly, considering the whole creation is the workmanship of a wise and good Agent, it should seem to become philosophers to employ their thoughts (contrary to what some hold) about the final causes of things; and I must confess I see no reason why pointing out the various ends to which natural things are adapted, and for which they were originally with unspeakable wisdom contrived, should not be thought one good way of accounting for them, and altogether worthy of a philosopher." — Vol. I. p. 466. (Ed.) In the work reviewed this passage from "A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge," Part I, is in Vol. I, p. 208 (§102), p. 210 (§106), and pp. 210-211 (§107). †14

32. After this how can his disciples say "that the true logic of physics is the first conclusion from his system"!

33. As for that argument which is so much used by Berkeley and others, that such and such a thing cannot exist because we cannot so much as frame the idea of such a thing, — that matter, for example, is impossible because it is an abstract idea, and we have no abstract ideas, — it appears to us to be a mode of reasoning which is to be used with extreme caution. Are the facts such, that if we could have an idea of the thing in question, we should infer its existence, or are they not? If not, no argument is necessary against its existence, until something is found out to make us suspect it exists. But if we ought to infer that it exists, if we only could frame the idea of it, why should we allow our mental incapacity to prevent us from adopting the proposition which logic requires? If such arguments had prevailed in mathematics (and Berkeley was equally strenuous in advocating them there), and if everything about negative quantities, the square root of minus, and infinitesimals, had been excluded from the subject on the ground that we can form no idea of such things, the science would have been simplified no doubt, simplified by never advancing to the more difficult matters. A better rule for avoiding the deceits of language is this: Do things fulfil the same function practically? Then let them be signified by the same word. Do they not? Then let them be distinguished. If I have learned a formula in gibberish which in any way jogs my memory so as to enable me in each single case to act as though I had a general idea, what possible utility is there in distinguishing between such a gibberish and formula and an idea? Why use the term a general idea in such a sense as to separate things which, for all experiential purposes, are the same? (Ed.) This is an early anticipation of Peirce's pragmatism, which is discussed in detail in [CP] V, Pragmatism and Pragmaticism. See especially 5.402, 5.453, 5.504n1 (p. 353). Cf. also 7.360. †15

34. The great inconsistency of the Berkeleyan theory, which prevents his nominalistic principles from appearing in their true colors, is that he has not treated mind and matter in the same way. All that he has said against the existence of matter might be said against the existence of mind; and the only thing which prevented his seeing that, was the vagueness of the Lockian reflection, or faculty of internal perception. It was not until after he had published his systematic exposition of his doctrine, that this objection ever occurred to him. He alludes to it in one of his dialogues, but his answer to it is very lame. Hume seized upon this point, and, developing it, equally denied the existence of mind and matter, maintaining that only appearances exist. Hume's philosophy is nothing but Berkeley's, with this change made in it, and written by a mind of a more sceptical tendency. The innocent bishop generated Hume; and as no one disputes that Hume gave rise to all modern philosophy of every kind, Berkeley ought to have a far more important place in the history of philosophy than has usually been assigned to him. His doctrine was the half-way station, or necessary resting-place between Locke's and Hume's.

35. Hume's greatness consists in the fact that he was the man who had the courage to carry out his principles to their utmost consequences, without regard to the character of the conclusions he reached. But neither he nor any other one has set forth nominalism in an absolutely thoroughgoing manner; and it is safe to say that no one ever will, unless it be to reduce it to absurdity.

36. We ought to say one word about Berkeley's theory of vision. It was undoubtedly an extraordinary piece of reasoning, and might have served for the basis of the modern science. Historically it has not had that fortune, because the modern science has been chiefly created in Germany, where Berkeley is little known and greatly misunderstood. We may fairly say that Berkeley taught the English some of the most essential principles of that hypothesis of sight which is now getting to prevail, more than a century before they were known to the rest of the world. This is much; but what is claimed by some of his advocates is astounding. One writer says that Berkeley's theory has been accepted by the leaders of all schools of thought! Professor Fraser admits that it has attracted no attention in Germany, but thinks the German mind too a priori to like Berkeley's reasoning. But Helmholtz, who has done more than any other man to bring the empiricist theory into favor, says: "Our knowledge of the phenomena of vision is not so complete as to allow only one theory and exclude every other. It seems to me that the choice which different savans make between different theories of vision has thus far been governed more by their metaphysical inclinations than by any constraining power which the facts have had." (Ed.) See Helmholtz's Treatise on Physiological Optics, §33. †16 The best authorities, however, prefer the empiricist hypothesis; the fundamental proposition of which, as it is of Berkeley's, is that the sensations which we have in seeing are signs of the relations of things whose interpretation has to be discovered inductively. In the enumeration of the signs and of their uses, Berkeley shows considerable power in that sort of investigation, though there is naturally no very close resemblance between his and the modern accounts of the matter. There is no modern physiologist who would not think that Berkeley had greatly exaggerated the part that the muscular sense plays in vision.

37. Berkeley's theory of vision was an important step in the development of the associationalist psychology. He thought all our conceptions of body and of space were simply reproductions in the imagination of sensations of touch (including the muscular sense). This, if it were true, would be a most surprising case of mental chemistry, that is of a sensation being felt and yet so mixed with others that we cannot by an act of simple attention recognize it. Doubtless this theory had its influence in the production of Hartley's system.

Hume's phenomenalism and Hartley's associationalism were put forth almost contemporaneously about 1750. They contain the fundamental positions of the current English "positivism." From 1750 down to 1830 — eighty years — nothing of particular importance was added to the nominalistic doctrine. At the beginning of this period Hume was toning down his earlier radicalism, and Smith's theory of Moral Sentiments appeared. Later came Priestley's materialism, but there was nothing new in that; and just at the end of the period, Brown's Lectures on the Human Mind. The great body of the philosophy of those eighty years is of the Scotch common-sense school. It is a weak sort of realistic reaction, for which there is no adequate explanation within the sphere of the history of philosophy. It would be curious to inquire whether anything in the history of society could account for it. In 1829 appeared James Mill's Analysis of the Human Mind, a really great nominalistic book again. This was followed by Stuart Mill's Logic in 1843. Since then, the school has produced nothing of the first importance; and it will very likely lose its distinctive character now for a time, by being merged in an empiricism of a less metaphysical and more working kind. Already in Stuart Mill the nominalism is less salient than in the classical writers; though it is quite unmistakable.

§5. Science and Realism